If I had a dollar for every time in my life where I referred to myself as a “jack of all trades, master of none”, I would be in N’Awlins delighting in jazz, café au lait and beignets.

Yet here I am, at home, and becoming more and more comfortable with the identity of the “auld skald”, and the autistic polymath.

I’ve written about “need for cognition”. Even though my autism went undiagnosed for 51 years, the traits were still there, and “need for cognition” was and is definitely one of them.

As a result, in my now 52 years, I’ve accumulated a lot of knowledge. Some of it just surface knowledge, and some of it is deep knowledge. Practically, it means I can talk to almost anyone about almost anything (except sport… sorry. )

What is polymathy?

The Cambridge Dictionary online defines a polymath as “a person who knows a lot about many different subjects.

Linguistically, it comes from Greek, poly mathēs, meaning “having learned much”, from poly (many) and paths (knowledge or learning).

ChatGPT tells me that the term came into use in the Renaissance period to describe individuals who excel in multiple fields of study, embodying the idea of Renaissance humanism, which emphasized a well-rounded education.

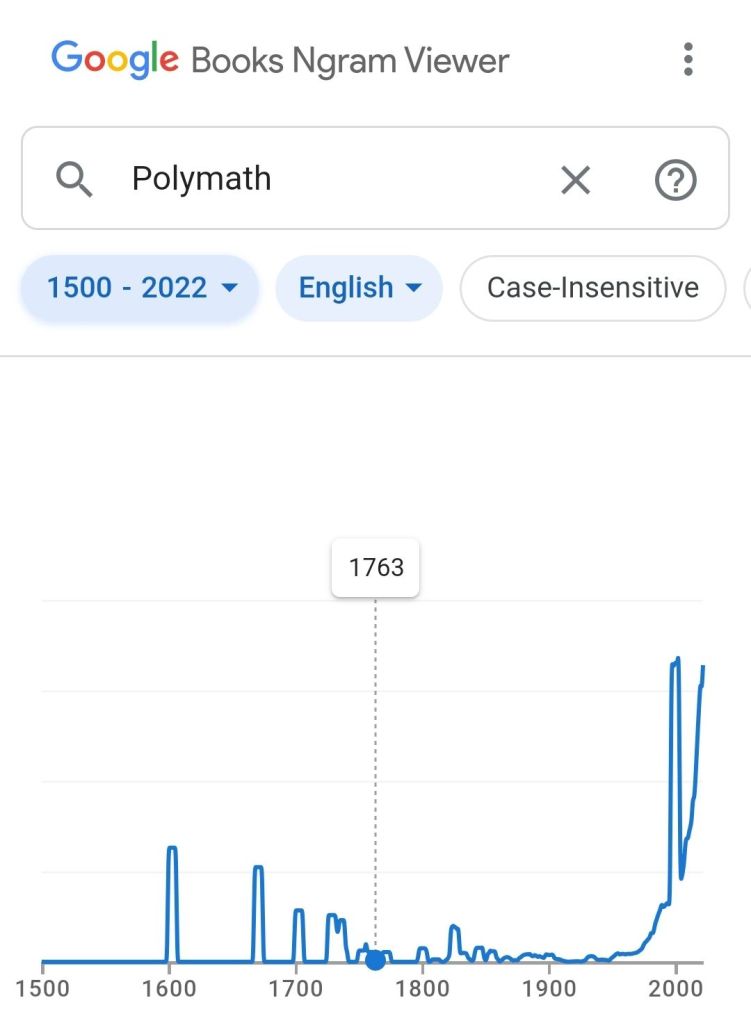

Google Ngram viewer shows this trend in usage over the last 500 years. We can see here a spike in usage in the last 20 years, possibly coincident with a broader societal focus on diverse ways of thinking, including greater awareness of neurodivergent conditions such as giftedness, autism and ADHD, as well as increased attention to mental health.

A retrospective look at polymathy (courtesy of ChatGPT).

(ChatGPT dialogue is shown in blue.)

Throughout history, several individuals have been regarded as polymaths due to their mastery of various disciplines. Some of the most famous include:

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) – Known for his extraordinary contributions to art, science, engineering, anatomy, and invention, Da Vinci is often considered the epitome of the polymath ideal.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) – A Greek philosopher who made significant contributions to logic, metaphysics, ethics, politics, biology, and many other fields.

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) – An Italian scientist and polymath, Galileo made groundbreaking discoveries in astronomy, physics, engineering, and mathematics.

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) – An American polymath, Franklin was an inventor, scientist, diplomat, writer, and political theorist, contributing to fields such as electricity, politics, and philosophy.

Marie Curie (1867–1934) – A physicist and chemist, Curie made pioneering contributions to radioactivity, and she was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, and the only person to win it in two different scientific fields.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037) – A Persian polymath, Avicenna made important contributions to medicine, philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy.

Female polymaths

Of course, the bias in the LLM and algorithms showed up, so I challenged ChatGPT to list more female polymaths, in addition to Mme Curie. It furnished this.

Hypatia of Alexandria (c. 360–415 CE) – A renowned philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer in Ancient Alexandria, Hypatia made significant contributions to mathematics and astronomy and was an influential Neoplatonist philosopher. She also taught a wide range of subjects, from philosophy to mechanics.

Émilie du Châtelet (1706–1749) – A French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher, Du Châtelet made important contributions to the study of energy and translated Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica into French, which remains the standard translation. Her work in physics helped lay the foundation for later studies in energy conservation.

Ada Lovelace (1815–1852) – Often regarded as the first computer programmer, Lovelace was a mathematician and writer. She worked on Charles Babbage’s early mechanical general-purpose computer, the Analytical Engine, and her notes included what is recognized as the first algorithm intended to be processed by a machine.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) – A German abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, and naturalist, Hildegard wrote extensively on theology, medicine, botany, and music. She also composed a large body of music and is considered one of the earliest known composers in Western music history.

Sophie Germain (1776–1831) – A French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher, Germain made significant contributions to number theory and elasticity theory. Her work in mathematics helped pave the way for the development of modern number theory, and she was a pioneering figure in mathematical physics.

Mary Somerville (1780–1872) – A Scottish scientist and polymath, Somerville made significant contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and physics. She was one of the first women to be admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society and worked on subjects ranging from celestial mechanics to electromagnetism.

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) – Known primarily as the founder of modern nursing, Nightingale was also a statistician, social reformer, and writer. She used her knowledge of statistics to revolutionize healthcare and hospital sanitation practices, applying her analytical skills to improving public health.

Laura Bassi (1711–1778) – An Italian physicist and academic, Bassi was one of the first women to earn a professorship at a European university. She made important contributions to physics, especially in the areas of electricity, mechanics, and hydraulics.

These women not only excelled in multiple disciplines but also often broke significant barriers in fields traditionally dominated by men, demonstrating their polymathic brilliance in various intellectual pursuits.

Of course, in the modern era, we cannot forget Hedy Lamarr, the actress of the 1930s and 1940s who developed frequency-hopping spread spectrum, which is a foundation piece for modern tech such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, mobile telephony and GPS.

And yet

Do current education practices encourage or discourage polymathy? Certainly, in the tertiary sector, knowledge is often siloed between faculties, and interdisciplinary undergraduate study is usually by way of a dual degree.

So, as a so-called “failed” mature-age university student, why do I still identify as a polymath? Quite simply, because the label fits.

I’ve had passengers who were chemical engineers, anaesthetic nurses, and psychologists, and so many more, and I’ve been able to engage with them in meaningful conversations, drawing on my varied background and curiosity. I can connect and ask questions.

I chat with passengers who are high school students about their studies, helping them with revision or exam prep during the drive.

My “magpie mind”, as I call it, along with my need for cognition, a lifelong love of learning, and just being a bookworm, makes me a polymath.

These days, my learning passions are inspired by research I read about, and by my autism diagnosis. In the last year, I’ve learned anew, and deepened my knowledge, in topics such as quantum mechanics, social issues, the DSM-5-TR, food chemistry, neurology, psychology, biology, philosophy, and quantum biology. I’m by no means an expert in any of these topics, but…

Jack of all trades, master of none, but oftentimes better than master of one

I’ll leave you with the poem that abounds on social media, author unknown.

“What the World Needs is…More Polymaths”

What the world needs is…

More polymaths—

A convergence of minds like Da Vinci, weaving art and science,

Stitching the fabric of existence with threads of varied hues,

Uniting the fragmented knowledge into a cohesive tapestry.

What the world needs is…

An embrace of interdisciplinary thought,

Where physics dances with poetry,

And mathematics sings in the language of the cosmos.

To break free from the silos of specialization,

And nurture minds that wander through the gardens of diverse fields.

What the world needs is…

The curiosity of a child in every adult,

An insatiable thirst for learning,

An unquenchable desire to connect the dots

From the quantum realms to the celestial spheres.

To see the beauty in equations and the logic in art,

To marvel at the symmetry of nature and the chaos of creativity.

What the world needs is…

A rejection of the notion that mastery demands singularity,

An affirmation that the Renaissance spirit is not antiquated,

But a beacon for modernity.

To champion the polymath as a model for innovation,

To cultivate minds that think both broadly and deeply,

Balancing the scales of depth and breadth.

What the world needs is…

Remedies for the ailments of narrow vision,

Educational systems that foster curiosity over conformity,

Institutions that reward holistic thinking,

And societies that celebrate the synthesis of ideas.

To create spaces where collaboration thrives,

And the cross-pollination of disciplines bears fruit.

What the world needs is…

Progressions from fragmentation to integration,

From compartmentalization to connection,

From silos to synergies.

A world where the polymathic mind is not a relic,

But a harbinger of a future

Where solutions are as diverse as the challenges we face.

What the world needs is…

The profound insight that every question answered

Begets a thousand more unasked,

That the pursuit of knowledge is an endless journey

With no final destination.

To understand that the polymath is not just a thinker,

But a seeker, a dreamer, a builder of bridges

Across the chasms of ignorance.

What the world needs is…

To recognize that the true genius lies

Not in knowing all the answers,

But in asking the right questions,

In seeing the interconnectedness of all things,

And in daring to explore the spaces between.

What the world needs is…

More polymaths—

For they are the torchbearers of wisdom,

Illuminating the path to a more integrated,

Innovative, and insightful world.

A world where knowledge is not hoarded,

But shared, expanded, and celebrated,

In a symphony of human potential.