My personal story and journey to discovering my autism in 2023, aged 51, actually started in 2019.

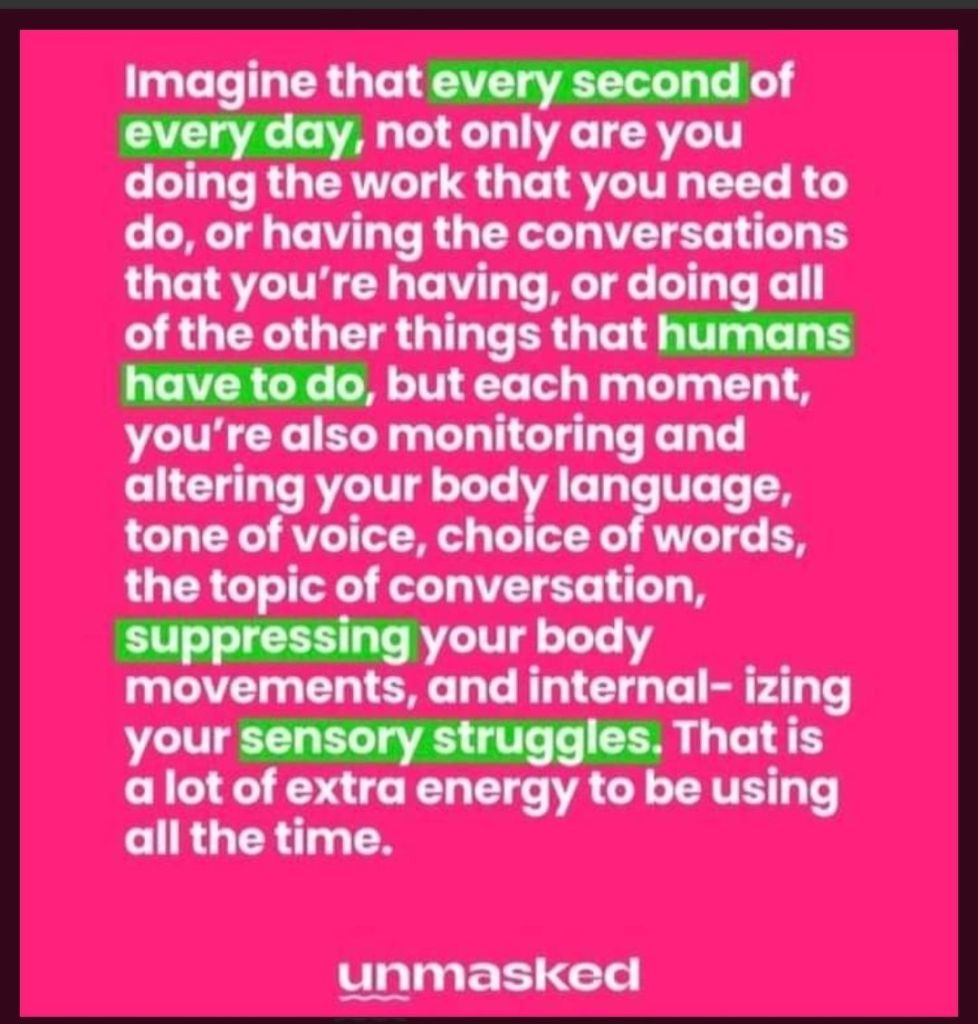

Many women, like me, develop almost bomb-proof masking, or camouflaging, over a lifetime of trying to fit in. But, as was the case for me, there comes a time when life events exceed the capacity of the camouflaging.

My masking cracked after my husband died, in June, 2019, following a 15 year decline with Huntington’s Disease. The cracks in my masking didn’t appear in the immediate aftermath, but very close to it.

I got through the day of his funeral by reciting “I have a dress with pockets and a pretty hanky (handkerchief).”

Black humour and a dry, cynical tone of voice became my coping mechanism, my new identity, my new mask.

By late August, after a few other events, I was reciting this when people asked how I was going:

- 29 June, my husband died

- 10 July was his funeral

- 10 August, I interred his ashes on his dad’s grave, next to his mum’s ashes

- 17 August my cat died

The dispassionate, sing-song way I recited this was a pretty big pointer, for those who knew autism, that I was autistic.

Covid-19 came along a few months later, with no chance of following up.

My masking was somehow holding together. I describe it as a shattered plate stuck together with sticky tape. My autism was peeking through, stronger and stronger.

It wasn’t until I simply couldn’t do a university assignment, a rhetorical analysis of a poem, that I started to believe that something was “wrong”.

Three failed uni courses later, I broke.

Three referrals later, I had an appointment with a neuropsychiatrist, about whom I’ve written in another post. That person considered sleep apnoea and temporal lobe epilepsy. At no stage did he produce a check-list of any kind to look for autism.

Now, I was at breaking point several times between 2019 and 2024, but I still had a fairly easy run at getting my diagnosis… unlike other autistic people I know.

A friend’s story

A friend of mine, a nonverbal teenager, spent years in and out of children’s psychiatric hospitals with multiple misdiagnoses before she got her autism diagnosis. Her story and my own undiagnosed story prompt me to think about all the three year old girls out there, starting to show their true, autistic selves.

Consider this scenario

Imagine, for a moment, we are peeking into the life of a young, undiagnosed autistic girl.

At three years of age, she has delayed speech development. Her parents arrange an overwhelming cavalcade of speech pathologists, occupational therapists, psychologists and psychiatrists. The girl’s her speech is further delayed because the sensory issues of her undiagnosed autism makes it impossible for her to speak; her own speech adds to her sensory overload.

In an effort to find out why she is not speaking, an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat specialist) does a nasolaryngoscopy, where a small camera attached to a flexible tube is inserted through the nostril to examine the larynx and vocal folds for a physical problem.

For her, the sensory overload of this going up a nostril and down the back of her throat is excruciating. She is red-headed and undiagnosed autistic, which means that she has a lot of resistance to the local anaesthetic, and it isn’t working. She struggles, and is held down by four people, including her parents, to stop her from struggling while they conduct this test.

Building trauma on top of sensory overload, but she is a child, overwhelmed, terrified and with a tube in her throat, she can’t scream.

Afterwards, she can do nothing but scream and jump, stimming, trying to regulate, but further abrading her throat, still painful from the nasolaryngoscopy. And then, she returns to her non verbal ways, with a deep distrust of doctors, and even her parents, after they helped hold her down when she was in pain.

Her mind, though, is razor sharp. She doesn’t need a voice to think. She writes, filling journal after journal. But sensory issues plague her, including ARFID. As she grows up, dieticians and nutritionists and allergen specialists are added to the phalanx of specialists.

At 6 years old, she refuses school. The sensory overload paralyses her, and she is assessed for epilepsy.

At 9 years old, she is hospitalised with suspected anorexia nervosa, with her continued refusal to eat anything except a few foods.

At 10 years old, having learnt from other, older girls in the hospital, she self harms, starting with skin picking, and developing to slapping herself. She adopts sensory seeking behaviours, seeking pain to silence the voice in her head, her inner monologue.

At 11 years old, she is committed to a psychiatric hospital, for fear of her committing suicide. Her food refusal results in a gastric tube being authorised by her parents.

At 12 years old, still in hospital, she develops gender dysphoria and is flagged for borderline personality disorder.

At 13 years old, a trauma-informed psychologist, who is AuDHD, starts working with her. This person, with her own autistic compassion, empathy and sense of justice, gives different labels to the girl’s behaviours. Stimming, sensory seeking, ARFID, hyperlexia. This psychologist works with the hospital and the girl’s parents to have her moved to a different facility. Trust develops slowly.

A diagnosis of autism with voluntary non verbalism is made for the girl. Medications are wound back, the gastric feeding tube is removed. The girl has an opportunity, for the first time, to learn about autism and her type of autism; her sensory sensitivities and also her sensory joys, including food. Her hyperlexia is celebrated, her writing encouraged, and she discovers watercolour painting, and then the art of paper-making.

At 14 years old, she returns to her family home. Old patterns emerge, and within months, she is back in the facility, at breaking point again. This time, though, she is in autistic burnout, with acute mental paralysis. She spends most of her days sitting on her bed, staring at the ceiling, sometimes wrapping her arms around herself and rocking.

Let’s leave it there, as you can by now, I hope, get a sense of the trauma, the PTSD, not only for this girl, but her parents. Bear in mind that autism is genetic, so one of her parents may now be struggling with her or his own diagnosis of autism or ADHD.

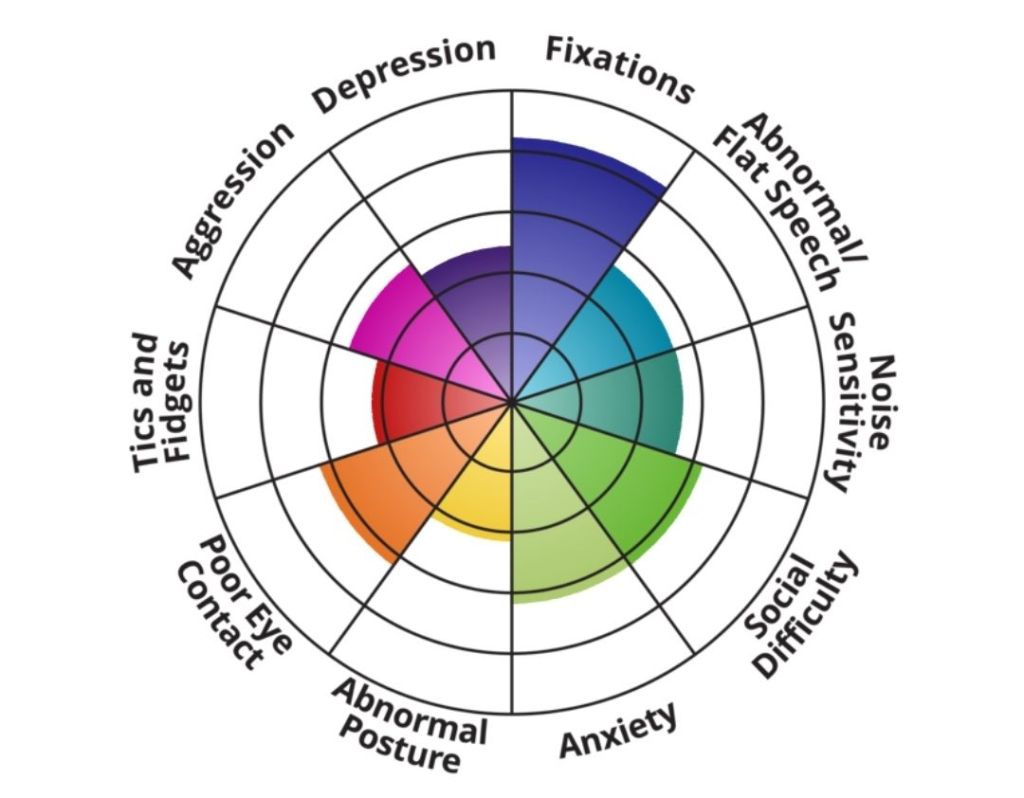

Look at the number of misdiagnoses for this hypothetical girl, when all along, it was undiagnosed autism.

Why is it that so many women and girls are not diagnosed until they have reached their breaking point?

ChatGPT’s take on late diagnosis and misdiagnosis

“The delay in diagnosing autism in women and girls often stems from several factors. One major reason is the way autism manifests differently in females compared to males. Traditionally, autism has been studied and diagnosed based on male-centered criteria, leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in females.”

And that’s true. But it doesn’t reflect the emotional, psychological and even physical damage from misdiagnosis. Look, again, at our hypothetical girl. How much damage, how much trauma, how much injury, do she endure before her diagnosis?

My autistic sisters, I see you, I hear you.