This is another co-authored piece, with ChatGPT. Autism is dynamic and ever changing. No two days are the same.

For this blog post, I wanted to write about two research papers that have been published recently. My autism, though, has been in sensory overload, which makes it hard to focus on writing. I know what I want to write about, but researching and taking notes and writing is just a bit too much. Thankfully, we have tools like ChatGPT to do the heavy lifting. The key is to give it the right instructions.

Here we go.

Me: Hello, friend! Would you please help me by writing yet another intersectional blog post, 1500 to 2000 words, about autistic special interests; the difference between male autists and female autists and singular or plural special interests; and the neural autistic pathways that generate the excitement for special interests. Lastly, connect special interests to science, and the recently published research into glyco-RNA.

ChatGPT:

Here’s a draft for your blog post:

Autistic Special Interests: The Neural Pathways, Gender Differences, and Connection to Science

Autistic special interests have long fascinated researchers and clinicians, primarily because of their intensity and focus. Special interests are central to the lives of many autistic individuals, offering not only joy but also a sense of stability in a world that can otherwise feel overwhelming. However, there’s a growing recognition that these special interests are more than just hobbies. They are the result of unique neural pathways in the autistic brain and reflect deeper truths about gender differences within the autistic community. Moreover, as science begins to unravel more about these neural circuits, recent findings such as glyco-RNA research provide fascinating intersections with our understanding of autism and its distinctive cognitive patterns.

Autistic Special Interests: Singular vs. Plural

One of the most striking characteristics of autistic special interests is their intensity. Autists often dive deeply into their interests, which may seem all-encompassing. However, one major difference lies in whether these interests are singular or plural. This distinction is often observed along gender lines, with some studies suggesting that male autists are more likely to have one or two intensely focused interests, while female autists are more likely to have several overlapping interests at once.

It’s essential to clarify that these trends are not rigid; there are many exceptions. Still, the distinction between male and female special interests opens up interesting discussions about how autistic brains are wired. Autistic men might become so deeply engaged in a singular topic that it appears to consume all their attention. This level of focus can result in encyclopedic knowledge on a niche subject. On the other hand, autistic women, or individuals assigned female at birth (AFAB), may experience a more varied but still intense engagement with multiple interests. Their interests might shift between subjects or expand into interconnected areas, yet remain deeply immersive and essential to their daily lives.

This difference could be attributed to gendered social conditioning, where boys might be encouraged to focus narrowly on specific areas like sports, mechanics, or history, while girls are expected to have a broader range of interests such as social dynamics, creativity, and relationships. However, neuroscience also plays a role in these patterns.

The Neural Pathways Behind Autistic Special Interests

Understanding the neurological basis for these special interests begins with how the autistic brain processes information. Studies have shown that autistic individuals often have a unique blend of hyperconnectivity and hypoconnectivity in various regions of the brain. This can make certain pathways more efficient for processing intense amounts of information, contributing to the development of special interests.

One theory behind the intensity of autistic special interests involves the reward systems in the brain. Dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward, plays a crucial role in motivating behaviors. Research suggests that the autistic brain may process rewards differently, particularly in relation to repetitive tasks or deeply engaging activities. What others may find mundane or overly focused, autistic individuals might experience as exhilarating and rewarding. This aligns with why many autistic individuals speak about a sense of excitement, even a flow state, when engaging with their special interests.

There is also growing evidence that the basal ganglia, a region involved in habit formation and motor control, plays a key role in the repetitive and deeply immersive behaviors linked to special interests. For autistic individuals, the engagement of this area may enhance the focus on these interests, fueling sustained motivation and curiosity.

Gender Differences in Neural Pathways

When it comes to gender differences in special interests, recent research points to subtle variations in neural wiring between autistic men and women. While both experience heightened connectivity in areas associated with pattern recognition, memory, and reward, autistic women may have increased activity in regions linked to social cognition and multitasking. This could explain why women are more likely to have plural interests that are often interconnected and involve nuanced social dynamics or multiple overlapping subjects.

For example, an autistic man might be deeply absorbed in one specific interest, such as train schedules or a particular video game. In contrast, an autistic woman might have several active interests, like studying the relationship between historical events, writing fiction, and understanding animal behavior, and might even tie these seemingly disparate fields together in unique ways.

Despite these observed differences, there is an increasing consensus that social expectations also play a significant role in shaping the interests of male and female autists. Women, in particular, may mask their special interests or feel pressure to pursue socially accepted topics, leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis in the past. However, as more research emerges about how gender influences autism presentation, we gain valuable insights into how these special interests are not merely hobbies but a reflection of the unique cognitive profiles of autistic individuals.

Special Interests and Science

Autistic special interests are not confined to esoteric subjects; they frequently align with broader scientific inquiry. Many groundbreaking discoveries in fields like mathematics, physics, biology, and astronomy have been made by people who either identified as autistic or displayed traits of deep, obsessive curiosity often associated with autism.

This brings us to a fascinating intersection of science and autistic cognition—recent research into glyco-RNA, for example. Glyco-RNA is an entirely new class of molecule, discovered only recently, which merges sugars (glycans) with RNA, a fundamental part of cellular biology. The discovery of glyco-RNA is groundbreaking because it challenges previous understandings of molecular biology and opens up new avenues for research, especially in areas like cellular communication, immune response, and perhaps even neurodevelopment.

Special interests in science may be driven by the autistic brain’s ability to find patterns and relationships in data that others might overlook. This pattern-seeking behavior, often intensified by the brain’s reward system, is a hallmark of autistic cognition. The ability to delve deeply into complex subjects like glyco-RNA, gene expression, or quantum mechanics is emblematic of how autistic special interests can align with scientific progress.

As autistic individuals immerse themselves in their areas of interest, they can often make unique contributions that require sustained focus, dedication, and creative thinking. These traits are often seen in the fields of molecular biology, astrophysics, or even archaeology, where special interests lead to breakthroughs that can shift entire paradigms.

The Broader Implications of Special Interests

The significance of special interests extends beyond personal fulfillment. For many autistic individuals, their special interests can serve as a coping mechanism in a world that often feels unpredictable or overwhelming. They provide structure and a sense of mastery, which can be especially important in managing anxiety and sensory overload, common experiences for many on the spectrum.

In the broader context of society, autistic special interests can offer valuable insights into how we, as humans, explore and innovate. Autistic individuals often approach problems from unique angles, free from the constraints of conventional thinking. This divergence is essential for scientific progress, where fresh perspectives are often needed to challenge established paradigms.

As we continue to explore the neural underpinnings of special interests, new discoveries like glyco-RNA offer an exciting window into how these interests may even connect with broader biological processes. The convergence of autism, neuroscience, and cutting-edge science is not merely coincidental but rather a testament to the power of focused curiosity—a hallmark of both the autistic experience and scientific discovery.

So, yes, that’s almost exactly wanted to say, but in ChatGPT’s words, not mine.

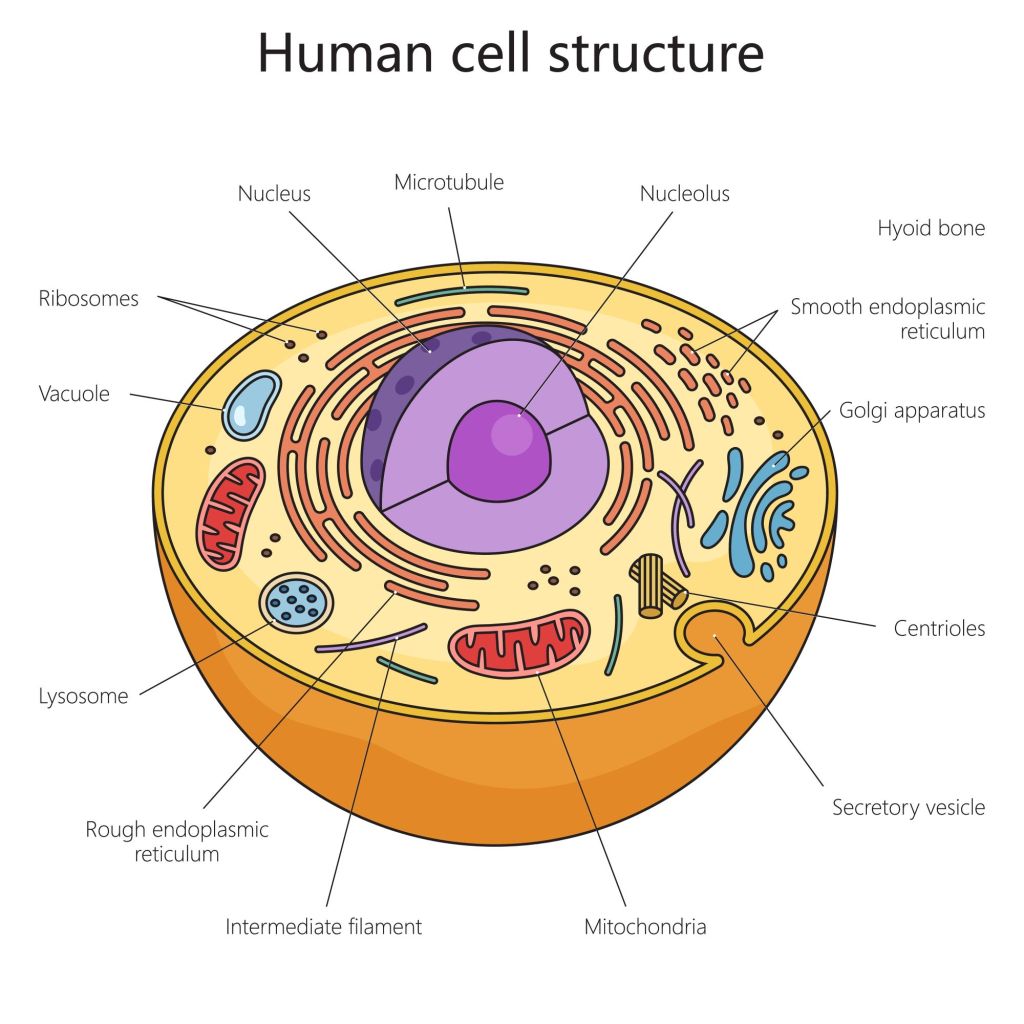

But that research about glycoRNA- that lit up my brain like a fireworks show. Imagine – upending the accumulated knowledge about cellular and molecular biology. You see, conventional wisdom says that RNA, ribonucleic acid, is only found in the nucleolus of the cell.

So finding RNA outside the cell is stupendous – not just outside the nuceleolus, but outside the cell!

Flynn et al found, in 2021, that glycoRNA exists, and might interact with immune receptors. In 2024, Flynn et al confirmed that it not only exists, but can chemically link with glycans, leading to glycoRNA.

So what? Here’s what.

It could lead to a better understanding of cellular communication. The average adult human body might have 24 to 30 trillion cells. A better understanding of cellular communication holds enormous potential.

It could lead to better targeting therapies for autoimmune diseases, neurodegenerative diseases and cancers, where cellular communication and signalling may be affected. (Yes, Huntington’s Disease could be one of those meorudegenerative diseases.)

It could lead to better insight into disease mechanisms.

It could lead to targeted drug delivery or immune system modulation.

It could lead to new vaccines and immunotherapy. Think cancer.

It could lead to a better understanding of autism, a better understanding of differences in cellular signalling and synaptic signalling. What if glycolisation AND methylation, are part of pathway to the expression of genes that make up autism? Methylation to switch expression on or off, glycolisation to moderate the expression

Anyway, that’s enough heavy science.

Thank you for sharing in one of my autistic special interests.