On a seemingly ordinary Monday afternoon in May 2019, my phone rang, and it was the nursing home calling to inform me about yet another choking episode for Allan. The speech pathologist, who happened to be on-site, had made the decision to call an ambulance, and Allan was en route to the emergency department. Little did I know that this would be the start of a rollercoaster of emotions that would define the coming days.

The hours that followed were filled with nerve-wracking phone calls to the emergency department, as I advocated for Allan’s wishes and his intention to refuse certain medical interventions. It seemed like everything was back to normal when I received a call from the ED, reassuring me that Allan’s scans showed clear lungs, and he was on his way back to the nursing home.

However, the next morning, the nursing home threw me a curveball by asking what they should do with Allan. It turned out the speech pathologist had declared him “nil by mouth,” and the nurse who called me said, “there’s no care directive, we can’t starve him, so what do you want us to do?” To say that I was shocked and angry would be an understatement.

Imagine my frustration, knowing that was indeed an advanced care plan that had been developed in consultation with the Clinical Manager and the GP. This plan had been established after the neurologist declared Allan to be in the palliative phase of his illness. I was left shaking, unable to drive, and in dire need of support. Thankfully, a dear friend came to my rescue, driving me to the nursing home.

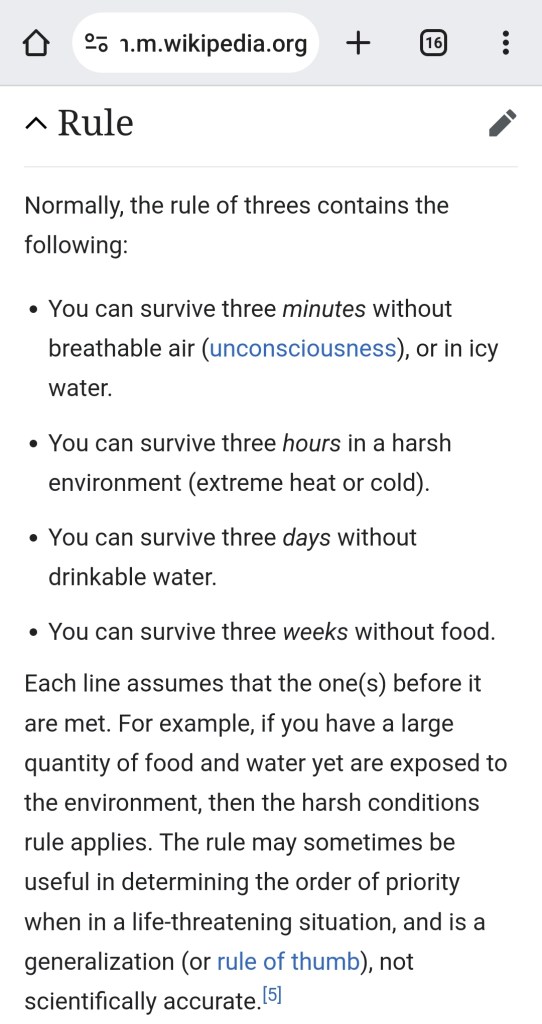

During a challenging afternoon, we confirmed Allan’s intentions, which included refusing a feeding tube, intravenous hydration, and antibiotics, opting only for pain relief. At this stage of his disease, Allan was nearly non-verbal, suffering from severe dysphagia, and had dropped to around 35 kilograms in weight. As someone with a background in occupational health and safety, I knew that without nourishment and hydration, he had only a few days left.

I began preparing for the inevitable, reaching out to Allan’s NDIS support coordinator and service providers, who proved to be invaluable. His NDIS plan was adjusted to ensure that a support person would be with him for 10 hours a day, so he wouldn’t be alone during his final days. The outpouring of support from these individuals was truly commendable.

I also started making arrangements with the funeral insurance provider and the funeral director, even organizing a removalist in advance to pack up Allan’s room and transport everything to my home. I took two weeks off work, anticipating the worst. I checked into the Mercure Gold Coast and prepared to make his last days as pleasant as possible.

Allan slept most of the following Tuesday, but when I called the nursing home on Wednesday morning, I was bewildered to learn that he had been fed and was resting comfortably. It contradicted the “nil by mouth” decision, and my anger grew over the lack of adherence to Allan’s wishes. I rushed to the nursing home, only to be told by the Clinical Manager that he had changed his mind, with no witnesses except her, and that the speech pathologist had amended the report to allow comfort feeding. Allan had not been provided with any additional pain relief.

This contradicted the GP’s previous approval of the “nil by mouth” decision, and the lack of proper documentation left me frustrated. It also meant that the 10 hours of daily personal care funded by the NDIS had to be discontinued.

After a whirlwind of events, I had to disconnect from the nursing home, although I remained committed to Allan. The experience had taken me on an emotional rollercoaster, swinging from preparing for the worst to a confusing state of uncertainty about Allan’s long-term outlook.

What were the failings in palliative care? Was it that a palliative care plan was not put in place, at that time, after his decisions on the Tuesday afternoon? Was it that I wasn’t sure if his wishes weren’t being adhered to? Was it that the confusion over the speech pathologist’s report? Was it that they didn’t take Allan’s wishes seriously at that point? Was it the GP’s failure to implement a terminal care plan?

In retrospect, this tumultuous period became a devastating “practice run” for Allan’s end of life, just six weeks later.